Gender Queer has made history this year as one of America's most banned books. Across the South, conservative parents and legislators have used the autobiographical graphic novel as evidence that LGBTQ+ literature is corrupting children and should not be allowed in public school libraries.

It was the perfect choice for our spring book club.

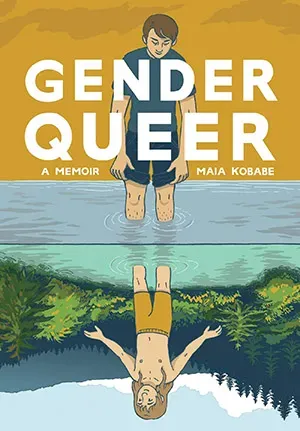

Gender Queer is a beautifully illustrated novel that depicts the life story of comic writer and art teacher Maia Kobabe (e/em/eir). E begins the novel with eir childhood, growing up in rural Northern California. Kobabe's choice to include stories from eir early childhood gives a subtle nod to the ways children are raised to experience and internalize gender norms from a young age. The stories also foreshadow Kobabe's future struggles with gender identity.

A love letter to Trans and Nonbinary kids

Kobabe's book is a love letter to Trans and Nonbinary children, an acknowledgment that they are valid.

Kobabe's book shares stories of a Genderqueer childhood, stories that can resonate with Trans and Nonbinary children who may not have adults or peers in their life with similar experiences. As of 2021, 60% of Trans children faced rejection by their families. Trans kids are also statistically nine times more likely to attempt suicide before the age of 18.

Activist Leslie Feinberg famously said, "Gender is the poetry we write with the language we are taught." Gender Queer is an artistic masterpiece showcasing one individual's journey to discover the language to explain eirself to the world. Kobabe leaves nothing out, describing eir encounters with sexual attraction, masturbation, and especially questioning. E also shows the love and support e had at home throughout eir growing-up years. Kobabe's parents were always accepting of their children, even if eir mother struggled to understand what being Nonbinary meant at first.

Kids do know about gender

Angela Kade Geopferd, a gender-diverse pediatrician, explained in their 2020 TED Talk that, despite common misconceptions by adults, children do conceptualize gender. "From the age of about two, kids can understand gender differences," Geopferd said. Kobabe demonstrates this in the first pages of the graphic novel when e talks about older children pointing out the differences between Kobabe, who was born female, and eir close childhood friend, Galen, a little boy.

Geopferd explained that by the age of three or four, children understand where they fit in the gendered categories society presents to them. Around this time, they also start to become socialized to understand what expectations they will face based on their gender.

"They have figured out their place in the world, and they are claiming it," Geopferd said of this time in early childhood development. "It shouldn't surprise you then that some Transgender kids are claiming their identities as young as three and four years old. They know the categories, they know how they should feel inside, based on their anatomy, and they also know that the way that they see themselves doesn't line up with those expectations."

"[Children] are first figuring out what they like," Geopferd said of this age, "and then, is it okay or not?"

Kobabe's experience

Kobabe depicts early childhood confusion around gender and societal messages about it. Despite being born and treated as a girl, e had interests often associated with boys, such as snakes. E was free to enjoy activities and styles often associated with boys and even took pride in the shoulder-length hair that left many classmates wondering what gender e was.

But in one panel, Kobabe illustrates the all-too-familiar experience of "cooties," the childhood plague that would forever separate em from close male friends, like Galen.

Kobabe also illustrates the experience of a child figuring out what it is e loves and then the repercussions of realizing society is quick to punish those who do not love the "right" things.

"By the time most kids are six and seven years old, they are conforming to traditional gender roles," Geopferd explained. "Girls are becoming more feminine, boys are becoming more masculine, they're starting to conform their hairstyles, the way they dress, the toys they play with, their peer groups to what society expects of them, based on their gender identities."

While this was happening to Kobabe's peers, e had different experiences. Eir parents were liberal and did not conform to all gender expectations. E grew up in a warm and accepting household that allowed em to dress, play with, and enjoy whatever e wanted.

However, Kobabe did receive messages about gender expectations from outside sources, like a teacher who punished em for playing without a shirt on in third grade.

"Kids who violate our expectations on gender are punished for doing so," Geopferd said. "The number one reason why kids are bullied at school is for gender-nonconforming dress or behavior."

Kobabe demonstrated this with eir own experiences of shame and confusion when e was told to wear a shirt when swimming and shave eir legs and underarms.

As Kobabe depicts eir adolescence and teenage years, more gendered issues e encountered surface, such as bras, periods, and crushes. A common theme throughout eir childhood was confusion because e did not have the language to describe where e fit on the spectrum of gender and sexuality. Eventually, e learned about Transgender people, but this only led to more confusion. E did not feel like a girl, but e also did not necessarily want to be a boy.

This experience is common among Nonbinary children. "I didn't think of myself as a boy," youth activist Audrey Mason-Hyde said, "but anything that was identified as female felt uncomfortable to me." This reflects much of the same sentiment Kobabe packs into Gender Queer. It is the story of a person coming of age and discovering just how nuanced gender may be.

Throughout the graphic novel, Kobabe laments eir naivety. From wearing deodorant to reading, e always felt like everyone else got the memo first when it came to growing up. However, a liberating childhood free from forced gender expression allowed Kobabe to grow and discover what e loved without as many influences from society.

Supportive family and neopronouns

Perhaps the most touching relationship in Gender Queer is the one Kobabe shares with eir younger sister, who is also Queer and supported her older sibling by giving em haircuts, introducing em to other Trans people, and even buying em eir first binder.

Kobabe's positive depictions of a supportive family provide hope for other Trans and Nonbinary children and can work as an instruction manual for family members curious about how to better support the LGBTQ+ person in their life.

E also shows the process of discovering LGBTQ+ vocabulary, but still not feeling like e fit into a particular box when it came to gender or sexuality. Even when e finally discovered the language to tell the world e was Nonbinary, "they/them" pronouns didn't feel right. Eventually, after becoming more enmeshed in the LGBTQ+ community, Kobabe learned about neopronouns and found that "e/em/eir" fit nicely.

The section leaves readers with the conclusion that as language and understanding continue to evolve, Genderqueer people can find a better vocabulary to express who they are to the world.

Gender Queer is a delightful book full of beautiful illustrations. It is no wonder conservatives oppose the book so strongly: in the right hands, it can be very dangerous to their agenda, as it provides hope, validation, and discourse for Trans youth. Gender Queer tells the reader, whoever they may be, that their existence is valuable to this world and does not require assimilation into fixed boxes. It is an essential read for any young child who may find themselves questioning where they fit in the world.