Zoë Bossiere never thought they'd grow up to be a writer, partially because they could never imagine themself growing up. Everything changed in college, however, when they fell in love with the page.

"I discovered creative writing as a field of study back when I was an undergraduate at the University of Arizona," they said in an interview with the SGN. Creative writing became an outlet in which Bossiere – a former trailer park kid – finally felt they belonged in the world of academia.

As they got more into creative writing, Bossier discovered a subset of the practice: creative nonfiction writing. "After taking a creative nonfiction class, I realized that I hadn't been writing fiction at all, but a thinly veiled memoir. So from that point on, I took the fiction elements out of my work and wrote nonfiction exclusively," they said.

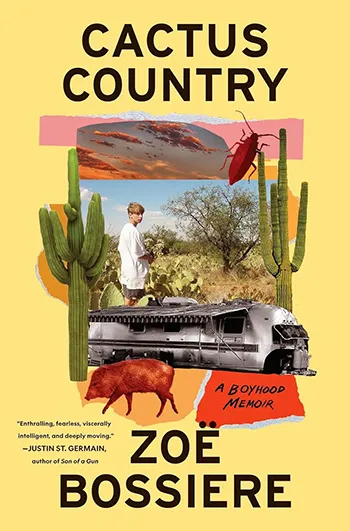

Eventually, they realized they had a story to tell – one of a boy growing up in Cactus Country, a desert trailer park community that became the book's title. "I knew it had to be a memoir. In my mind, there was no other way to tell it," they said.

Through stories about their childhood – a time when Bossiere, who is Nonbinary, identified as a boy – they were able to come to terms with their Trans identity and begin to process some of the trauma they encountered growing up.

Cactus Country is a beautiful and gut-wrenching memoir that shows readers what childhood is like through the eyes of a Trans kid. While it doesn't speak for all Trans experiences, it gives voice to one through gorgeous prose.

A story that had to be told

Writing a memoir, especially one about such personal topics, can be gutting. "To reflect on your life is to live it twice – or, in the case of writing a memoir, to live it over and over again with each new draft," Bossiere said.

"Some of the stories in Cactus Country's later chapters were particularly difficult for me to tell, because they contained traumatic events that I hadn't properly worked through before sitting down to write about them. It didn't help that much of this writing took place during the peak of the pandemic, when I was socially isolated from my usual support network of family and friends."

Throughout the process, Bossiere worked with a trauma writing specialist and a counselor, and received a grant from their university's Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department. "I don't know that I would have been able to write about certain things – and certainly not in as much depth – without those supports in place," they said. "Now, on the other side of that process, I feel more at peace about what happened, and I'm able to speak about the events depicted in Cactus Country publicly in ways I never could before, which is a great feeling."

Though revisiting some of their most traumatic experiences was incredibly difficult for Bossiere at times, they knew their story had to be told. "When I was a boy living in a trailer park way out in the Sonoran Desert, I couldn't picture myself as an adult – what I might look like or where I might go," they said. "I mean this in a very literal sense. I'd never met another Trans person. I didn't see myself in the characters on the TV shows I watched, or the music I listened to, or the books I read.

"The persistent thought that there might not be a future for someone like me was so terrifying and isolating that I spent a lot of time searching for a story that felt like it was written for kids like me, whose feelings about their gender didn't line up with their assigned gender at birth. I searched everywhere I could think to look, because I wanted to know how a story like mine would end. But I never found one."

Combating disinformation

While Trans kids today may have more on-page representation than Bossiere saw in the late '90s and early 2000s, there still isn't enough.

"Writing Cactus Country taught me so much, not just about my gender journey but about the Transgender spectrum more broadly," they said. "Trans culture is not the monolith that it was portrayed as in the '90s and '00s media. Today, Trans kids face more than the unknown – they have to wake up and continue to survive in a country where a growing cultural and political movement fueled by disinformation continues to target their existence. Telling stories in service of expanding the collective understanding of who and what Trans people are and are not is one way to combat that kind of disinformation.

"When I started writing Cactus Country, I wanted to tell the story the boy I was had been searching for. My hope now is for the book to reach readers who are also looking for a story like theirs, about the nuanced, often fluid complexities of gender and identity. At its best, I hope Cactus Country will help folks who have the same kinds of questions I did about who they are get one step closer to finding those answers."

Cactus Country will hit shelves on May 21, 2024. In the meantime, readers can find some of Bossiere's favorite works of creative nonfiction in the literary journal, Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction, of which they are managing editor. This year's special issue features exclusively Trans and gender-nonconforming writers, including Seattle's own Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore.