SGN Book Club explores LGBTQIA+ literature, new and old, from the fresh perspective of a Gen Z book enthusiast.

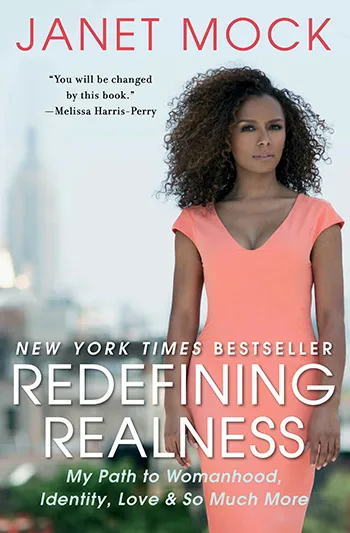

This week SGN's book club is reading the groundbreaking first memoir from LGBTQ+-rights activist and icon Janet Mock, Redefining Realness. First published in 2014, this honest, raw, and triumphant look at

Mock's coming of age – interspersed with true stories, introductions to Trans concepts and slang for cis readers, and hints at activism – has it all.

Mock begins her memoir with an introduction detailing her public coming out and describing why she felt her story could help other young Trans girls. Despite hearing countless messages from girls that her story inspired them, she admits that the Marie Claire article that introduced her as a Trans woman to the world was not her story.

The article perpetuated the idea that she was exceptional, flawless, and the rare Trans girl to make it out. She fit the profile of what mainstream cis, white, straight people were willing to accept a Trans woman as: beautiful, feminine, and passing.

"Being exceptional isn't revolutionary, it's lonely. It separates you from your community," Mock wrote. "It promotes the delusion that because I 'made it,' that level of success is easily accessible to all young trans women. Let's be clear: It is not."

Taking her story into her own hands, Mock decided to share her true coming of age – the messiness, the heartbreak, and the beauty she lived through as a young Trans girl growing up in Oakland and Hawaii.

The first section starts with Mock on a first date in New York in 2009. She describes the charm of the man she is quickly falling for, but behind all the excitement and joy of new love, she holds her identity close to her chest, worried about how the straight cis man will respond when she finally tells him she is Transgender.

Childhood in paradise

She immediately jumps back 30 years, to Honolulu, remembering an innocent youth set against the idyllic backdrop of paradise. She describes her family: her older half-sisters, her mother, and her grandmother. Despite living in a female-dominated environment, Mock recalls early memories of physical punishment for crossing the invisible gender line.

As these stories continue, readers get a better glimpse into her unstable home life. Her mother was a girlfriend first, often neglecting the children she already had at home to please and serve whatever man had charmed his way into her life.

Mock describes the early years of her childhood when one of those men was still her father. After her parents married, they had Janet and shortly after, her younger brother, Chad. The family of four, accompanied by an older half-sister, Cori, moved to Oakland after her father finished his stint in the Navy. There, Mock recalls some of her earliest memories: being taken to her father's mistress's house while he cheated.

Heartbroken by the infidelity of her husband, Mock's mother left him, taking Janet with her back to Hawaii but leaving her younger brother in California with their dad. Mock admits she did not miss her brother much, as she was thrilled to finally have all her mother's attention.

This, however, didn't last. Eventually, her mother found another boyfriend. After getting pregnant again, she decided to move in and start a family with him and send Janet away to California, forgetting about her and Chad, just as she had with her first two daughters.

Oakland masculinity

In Oakland once again, Mock recalls the constant battles she faced with her father, who attempted to force masculinity upon her. "My femininity was heavily policed because it was seen as inferior to masculinity," Mock writes. "My father, though he didn't have the words, couldn't understand why I would choose to be feminine when masculinity was privileged."

Her deviance in this regard led her to often feel like an outcast in her new family dynamic, in which her brother and father bonded over sports, the masculine Holy Grail. With nobody in her life who truly understood her, Mock became vulnerable to the prying eyes of others. "I later learned [what] predators have in their arsenal of affections: They can make an isolated, outcast child feel special."

The "special treatment" Mock refers to came from her father's girlfriend's teenage son, Derek. While he had originally paid her little mind, once Derek realized he could manipulate her, he took advantage of her sexually.

As she reflects on the abuse she suffered, Mock notes that her treatment as "other" by her father and brother may have inadvertently contributed to her vulnerability.

"Being or feeling different, child sexual abuse research states, can result in social isolation and exclusion, which in turn leads to a child being more vulnerable to the instigation and continuation of abuse," she writes. As a child, Mock believed she was "asking for" her abuse by being feminine and different from her brother, but as an adult, she realizes that she was entirely a victim, taken advantage by a boy who wanted to exert his power over her.

Texas, family, and Black womanhood

While Mock's life in Oakland with her father and brother was lonely and constantly filled with reminders that she did not fit the masculine ideal her father had for his children, everything changed when she turned 10 and the family moved to Texas. For the first time, Mock was surrounded by her father's family – aunts, cousins, and her grandmother – and she got a taste of what womanhood could look like.

"My grandmother and my two aunts were an exhibition in resilience and resourcefulness and black womanhood," she writes. "They rarely talked about the unfairness of the world with the words I use now with my social justice friends, words like intersectionality and equality, oppression, and discrimination. They didn't discuss those things because they were too busy living it, navigating it, surviving it."

Not only was her extended family a source for learning the intricacies of Black womanhood, but they also welcomed her into their circle. They allowed her to help cook, gossip, and even wear her female cousin's clothes from time to time. The women in Mock's life saw her for who she was and enabled her to explore her identity.

Unfortunately, her father still attempted to police Mock's gender expression up until the day things changed for her once again. She was 11 years old when her mother finally called back, after years of absence, requesting that her two children return to her in Hawaii.

Soon after, she boarded a plane with her brother and set off for a new life hundreds of miles away.

A girl from Hawaii

Mock saw her return to Hawaii as a way to reinvent herself. Unlike before, she decided to keep her hair short, wear only boys' clothes, and try to keep up with her brothers. "If I did these things, then Mom would never send me away again," she remembered. She blamed herself for her mother's neglect, just as she had blamed herself for becoming a victim of sexual abuse.

"On the road toward self-revelation, we make little compromises to appease those we love, those who are invested in us, those who have dreams for us," she writes. "I didn't have the words to define what I saw or who I was, but I recognized myself and often chose to dismiss her with the one question that pushed me to put the mask back on: Who will ever love you if you tell the truth?"

The answer to this question came to her in the form of Wendi, the only openly Trans girl at Mock's middle school. Wendi immediately saw through Janet's disguise, and the two became fast friends. Seeing Wendi live her truth so boldly and openly gave Mock the support she needed to take steps toward revealing herself to the world.

Wendi introduced Janet to fashion and makeup. She brought her with her to every doctor's appointment once she started taking HRT, and even provided her with under-the-counter pills until she was ready to come out to her mother.

With Wendi by her side, Mock found community among Hawaii's Trans women. "I was fortunate to meet someone just like me at such a young age," she recalled of her friendship with Wendi, which has lasted well into adulthood.

"Passing" and solidarity

Being able to access HRT at a younger age, before certain effects of puberty can become permanent, was important for Mock. As she reflects on the importance of "passing" to her younger self, she notes that "passing" is "based on an assumption that trans people are passing as something we are not. It's rooted in the idea that we are not really who we say we are, that we are holding a secret, that we are living false lives."

Placing more validity on Trans women who can "pass" is entirely transphobic and undermines the experiences of all Trans people. This way of thinking also privileges the select few fortunate enough to have early access to medication as more "authentic" than other Trans women.

While she knows it was wrong, Mock recalls the superiority complex she experienced once she was able to "pass," often ignoring her other Trans friends when out in public and feeding her self-worth with objectifying comments from men. "Objectification and sexism masked as desirability were a bittersweet part of my dream fulfilled," she recalls.

Mock let her privilege block her from solidarity with her other Trans sisters. She recalls looking down on those who relied on sex work to fund their transition journeys. Her perspectives shifted, however, when her home life became so tumultuous that she felt she had no other options than to follow in their footsteps.

Reflecting on her teenage experience as a sex worker, Mock writes, "My experience... is not that of the trafficked young girl or the fierce sex-positive woman who proudly chooses sex work as her occupation. My experience mirrors that of the vulnerable girl with few resources who was groomed from childhood, who was told that this was the only way, who wasn't comfortable enough in her body to truly gain any kind of pleasure from it, who rented pieces of herself."

Mock's memoir is the story of a remarkable woman who grew up against staggering odds to become an advocate for those she once saw herself above. Her story is one of triumph, love, friendship, and overcoming. Filled with references to great works of feminist literature, she leaves readers with a takeaway from theorist Simone de Beauvoir: "One is not born a woman, but becomes one." This is a story of womanhood shaping and forming. Mock's story is a testament to the triumph of womanhood and a must-read for any feminist coming of age today.