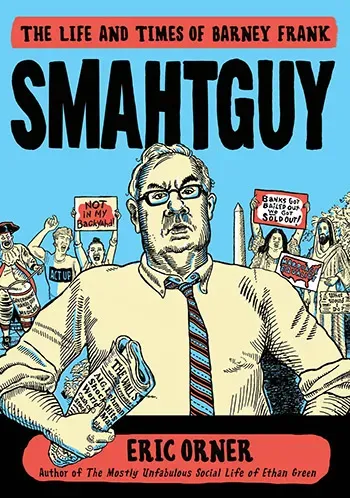

SMAHTGUY: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF BARNEY FRANK

ERIC ORNER

� 2022 Metropolitan Books

$25.99 / $13.99 (e-book)

224 pages

We probably should have seen what was coming back when House Majority Leader Dick Armey "accidentally" referred to Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts as "Barney Fag" in a 1995 interview. We should have seen the cracks in the façade of civility on the part of the American right wing that would erupt in a Vesuvius of shameless slander, insults, and defamation a decade and a half later.

The difference back then was that Armey at least had the cojones to apologize, as opposed to the double- and-tripling down employed by "conservatives" and Republicans of the red-hat variety nowadays. We could definitely use a token offering of shame and accountability nowadays – but more importantly, we need a Barney Frank right now.

A must-read for political junkies who also dig graphic novels, Smahtguy is relatable, humane, well researched, and sharp as a brass tack. Eric Orner is the ideal choice to graphically chronicle Frank: Gay, politically astute, and witness to the man in action firsthand, having been a one-time intern.

Not to mention, he's witty AF. His The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green is inarguably one of the funniest Gay-themed strips in the history of funny.

With Smahtguy, he also takes his subject dead seriously and gives equal consideration to both Frank's political and private lives, with ample helpings of the kind of saucy badinage that made Ethan Green so hugely enjoyable. (There's even a cameo of that strip's Hat Sisters in an early '70s Gay rights march scene, among nostalgia-inducing signs like "Gay Is Good" and "Better Blatant Than Latent").

Orner does justice to the "and times" part of the book's title, immersing the reader in the social and political landscapes of the '60s through the 2010s and making complex political issues comprehensible to even those most easily bored by the inner workings of government. This is not just a biography but a prescient look into the absurdity and actual work of politics. (Someone please draft Aaron Sorkin and put him to work on a miniseries based on this book now.)

Besides humor, Orner employs another technique that has come to be associated with LGBTQ and women cartoonists: the inclusion of various races, shapes, sizes, and appearances among background characters, making them a group of individuals and not just a milling crowd.

Orner also uses color uniquely: one page will have blue highlights, which segue into yellow on the next page, then pink on the next. A dash of rose taints the face of a bloviating colleague railing against a pot decriminalization bill Frank introduced. Splashes of color give added depth to scenes of people just sitting around talking. This proves far more effective than full color, which, with Orner's tightly packed, detailed art, would have overwhelmed the reader and distracted from the narrative. It's a clever device that keeps the eye awake in a way just black-and-white wouldn't have accomplished.

Orner also has a keen eye for detail, from period pieces like peace-sign necklaces and platform wedgies to the brutalist architecture of Boston City Hall, snarky newspaper headlines, and campaign posters of Frank proclaiming "Neatness Isn't Everything."

Frank's background

A lifelong liberal from a left-leaning New Jersey family, Frank fought for every progressive cause under the sun, from eliminating race-based gerrymandering to public transportation to the protection of sex workers to abortion rights.

He attended Harvard in the waning years of the "good old days," when Gays and Lesbians were branded "security risks" and not even JFK could show any interest in their civil rights. He made his political bones as a schlubby Jewish kid in the midst of Irish Catholic–dominated Boston, where the not-at-all-missed Louise Day Hicks openly expounded on "replacement theory" when it was just "white backlash."

Frank proved himself indispensable in Boston Mayor Kevin White's administration, and was even instrumental in curtailing violence in the wake of MLK's assassination by working with the mayor's office on televising a James Brown concert. And he wasn't cowed by the likes of Massachusetts Senate President Billy Bulger or his scarier brother Whitey, like most Boston Dems, thanks to his natural-born chutzpah and the memory of his truck stop–owning dad's brushes with Jersey wise guys. His skill at fighting mob-like tactics would serve him well against Republicans – and even members of his own party – throughout his career.

Even before coming out himself, he filed the first Massachusetts Gay rights bill, even before taking his seat in the state legislature, and later fought to repeal the criminalization of sodomy, which was torpedoed at the last minute by conservative hacks who thought it would be a hoot to wait until the last second to vote no.

But even this didn't slow Frank down. He went up against a John Bircher (for the young'uns, that's the equivalent of "MAGAot" in boomer-speak) in his first congressional race in 1980, when being unapologetically liberal against a right-wing lunatic was actually an advantage.

Frank was a true populist and a welcome alternative from the usual smarmy glad-handing. This was well illustrated in an encounter with some Vietnam vets, in which Frank took phone numbers for the purpose of personally contacting the VA on their behalf. As one vet put it, "No 'thank you for your service' bullshit. Weird."

The end of the closet

By page 123, you no doubt may be thinking, "When the hell is he going to come out already?" And well you might. After a mostly unfabulous run of missed or brief encounters, Barney entered into what he thought was a casual, uncomplicated relationship with a hot young hustler, "Steve," who used Barney's apartment to throw parties with other DC professional wastrels, leading to the notorious "bordello scandal."

The Moonie-owned Washington Times asked Frank point-blank if he had paid for sex with "Steve." Knowing the best defense was just plain honesty, he replied in the affirmative. This was the last thing the muck merchants anticipated, but contrary to their slavering expectations, Frank's candor was rewarded with overwhelming positive support, even in the worst years of AIDS and despite demands for his removal by those with far noisier skeletons in their closets (Gingrich, Hastert, Larry "Wide Stance" Craig).

This episode, plus being outed by homophobic homo congressman Bob Bauman (depicted as a trollish anti-Frank, complete with horns) and the AIDS crisis reminding him sharply of who he was, ushered in the end of Barney's long residency in the closet.

Frank would continue to fight the good fight during the rise of "neoconservatism," laying the groundwork for the legalization of same-sex marriage and serving as the Clinton White House's unofficial LGBT liaison (he would return their support by standing by Bill during the Lewinsky kerfuffle).

His work with Bush's Treasury Secretary Henry Paulsen on the 2008 banking crisis was an example of bipartisanship we're not likely to see again in our lifetimes (well, my lifetime, at least).

His prescience in seeing the inevitable pop of the housing bubble and his dogged persistence led to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill. The hearings on that bill are definitely a comedic highlight in Orner's book, with the Senate depicted in traditional Roman garb and attitude and Frank entertaining thoughts of the Ides of March and Maxine Waters' curt summation: "Getta load'a this shit" (if she didn't actually say it, she should have). The hard-won Dodd-Frank bill passes with the ghosts of LBJ and Frank's comrade-in-arms Tip O'Neill in celestial attendance.

The book closes with Frank's retirement from a jam-packed career and his marriage to Jim Ready – a joyous and welcome happy ending. Orner is a deft hand at depicting flirting, affection, and relationships in all their sweetness and messiness, and makes the reader feel as much a part of the reception revelry as any other guest, having been through a lot with Barney for 220 pages and realizing, as one wedding guest puts it, "You gotta love Barney Frank to like him."