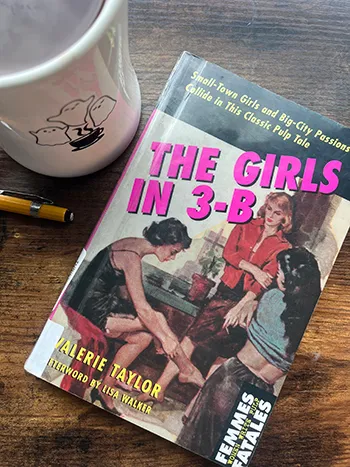

THE GIRLS IN 3B

VALERIA TAYLOR

© 2003 The Feminist Press

© 1959 Valerie Tayloe

$13.95

206 pages

Content warning: Sexual assault, pedophilia, incest, domestic violence

Sometimes the stories with "happy" endings are the saddest of all.

To summarize, three women from the sticks – Pat, Annice, and must-be-protected-at-all-costs Barby – go to Chicago to try to make their way. Pat works an office job, while Annice gets involved in the local beat scene and strives to be a poet.

They struggle under the weight of an internalized patriarchy they don't realize they're carrying, i.e., they're total pick-me girls. Pat talks about the older single women in her office enjoying each other's company with repulsion, unable to imagine that women without men could be happy. Annice detests the "ugly" girls in the beat movement, while lauding how attractive and intellectual the men's ugliness is.

After narrowly surviving predatory men, they find nice boys their parents would approve of and move back to the suburbs to start the family life they initially despised. Both had ambitions for independence and lives different than the ones their mothers lived, but, when faced with a world that sees them as consumables, they have fled back to what they originally thought of as stagnancy, seeing it now as stability. These characters' happy endings are happy according to their own expectations, but damn if they aren't tragic by mine.

Barby, the last roommate, is the sweet cinnamon roll of the group. She was sexually assaulted at 13 by her father's friend. She was unable to go to her mother, who had told her that to be assaulted is to be ruined. The only one who knows is her father, who has his own incestuous feelings toward her – unacted upon but tangible in every interaction. She's trapped by the norms of the nuclear family and suburban life. She struggles with debilitating migraines and feelings of worthlessness and inner rot. When she gets to the city, she revels in the anonymity. In her invisibility, she's safe.

At work, Barby meets a beautiful older woman, Ilene, who takes her out to lunches and eventually leaves a Gay romance novel at her workstation. Barby, curious and eager, devours it. In one telling scene, Barby reads this book on a davenport – a symbol previously of suburban rot, her assault, and her father's harassment – and, for the first time, she relaxes. The book ushers her into a world beyond the one she's known, into one where she can finally belong and feel secure, something she had never thought was possible for her.

A covert Gay novel slipped into her things by a mysterious older woman? If only every Queer landing could be so soft. Crucial to their relationship is that Ilene tells Barby she doesn't have to speak about her past. To love and be loved is a baptism of sorts, where what Barby thinks is rotten about herself is cleansed.

The Girls in 3B is notable for being the first book in which a Queer gets a happy ending. Arguably, the only happy ending. Barby and Ilene's relationship is the only one not saturated with deceit. Ilene is the only one to ask for consent. She alone acknowledges their difficulties and gives information that allows her partner to discover herself and make an informed decision. Barby, in turn, is honest about her attraction and expresses it.

None of this is allowed in straight 1950s relationships. Pat's fiancé, against Pat's firm refusal, still attempts to have sex with her – and Pat says that, if he hadn't, she wouldn't have felt desired. Pat's husband also doesn't know what it's like to be desired by a woman or to feel attractive; since women of the time aren't allowed to express desire, all he's learned is to push.

Beyond deceit, there's overt violence. Annice's husband tells her that he'll beat her if she cheats, and Annice tells him that she wouldn't respect him if he wasn't willing to beat a woman. Internalized patriarchy's a bitch.

They all find themselves safely ensconced in a home and with a partner by the end. Each of these happy endings is a refuge from an unwelcoming world, but that safety hinges on their isolation. None of them have friends or significant relationships outside of their partner. All of them go into their partnerships as a form of escape from something worse. The only option for women of this era in their circumstances was the abyss of domesticity and the prison of home.

In the end, I can only give these characters the same response I give when yet another straight friend announces their engagement to a milquetoast man: a pained grin and an "I'm happy you're happy."