Author Mac Crane started the journey toward their debut published novel over ten years ago. In 2013, though, Crane was a very different writer. They focused on poetry, which is where they got their first seed of inspiration for the novel, I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself.

"I was struggling with a lot of shame," Crane admitted. "I was fresh out of college, having trouble romantically, unsure of my footing in the world, and telling myself all these negative stories of who I am. I wrote this poem that said, 'If the shadows of everyone you'd wronged followed you around, would you still be so callous with people's hearts?'"

The image of haunting shadows resonated with Crane for years, even as their reflection on the poem changed. "It was something I thought would be helpful, but in retrospect, shaming yourself is not helpful. That visual stuck with me, that idea of literal shadows following you."

Five years later, they were still thinking about that eerie line of poetry. "In 2018, the first line of the novel popped into my head – just 'The kid is born with two shadows' – and I had no idea what that was," they said with a laugh. "I come up with so many first lines, and usually they just fall out of my head. This one was sticky. I was just like, what could that be? Why would somebody have two shadows? What kind of world is this?"

Eventually, the world revealed itself to Crane: a dystopian place where transgressors are punished by carrying additional shadows for every person they'd wronged. At the center is Kris, a woman grappling with grief as she takes on the sole parental role of raising the child whose birth left her a widow.

Continuing to live in their created world

Crane originally wrote Exoskeletons as a short story. "It was a 5,000-word story, but I wasn't done with it. I finished and submitted it to a few journals, but I couldn't stop thinking about it. I wanted to spend more time with these characters, deep in this world," they said.

They got the chance to spend more time in their created world later that year, after losing their job. "It was the first time I was unemployed in my adult life, and I thought, 'This is the time I gotta do it. I gotta write this novel,'" they said.

Crane treated the novel like a full-time job, writing six hours every day. "I wrote it very fast, and that's not something I prefer to do now, but I felt this ticking clock. I wrote it in three months. I just went for it, because I knew I'd never get this time again."

Their process slowed down after they signed with an agent. After the grunt work, Crane recalled there being a lot of waiting. In January 2023, ten years after their first hint of inspiration came in a poem, Crane was a published author with books on the shelf.

A lot has changed for Crane since they first started writing Exoskeletons. For one thing, they've now become a parent. "A lot of the book was me processing and working out some real-life things," they recalled. "When we started drafting this, we didn't have a kid, but we had just started the early stages of family planning. Some of Kris's journey was top of mind for me at the time: anxieties about parenting, am I going to be a good parent, what will this be like?"

Now the parent of a toddler, Crane admits they wouldn't change much in how they interpreted the central parent-child relationship in the novel. "The only thing I could do was sharpen those beginning details, like 'Oh, now I understand what blowouts are,'' they said with a laugh. "I had more of a visceral experience of parenting a newborn, but there's not much real parenting. It's all just an imagined future and imagined problems."

Holding up a mirror to society

While Crane admitted they didn't think they'd be very good at world-building when writing early drafts of their novel, they found that creating a dystopian world is a great way to say something about real life.

"Dystopian books have always resonated with me: the way there's always this beautiful distance. I've created a world that's different from our own, but because it's just different enough, I've created this distance that holds up this mirror and shows what our world is like," they said.

"It feels a little bit alien, but without that, I don't think you could connect with readers as much," Crane continued. "A lot of readers are distant to problems in our world. If I wrote a book that was just like, 'Our country is racist and sexist, homophobic, and transphobic,' I think a lot of people would be like, 'OK, great.'

"If you can create that distance where it's just different enough, [where] it's not possible, I feel like it just gives people that window in, where they're like, 'Oh that's eerily familiar.' It lets them have that discovery on their own instead of just shoving it down people's throats."

Crane hopes the book can function like a mirror to society and leave readers questioning how modern governments abuse power with punishment. "I want people to examine their relationship to shame and punishment, both internally – how we shame ourselves – and systematically, how we shame other people and police their behavior," they said. "We live in a society so obsessed with punishment and quick to punish. When someone does something wrong, even a toddler, we put them in the corner. Then there's incarceration.

"I want people to sit with this idea that there are other routes toward change and real growth. Even the idea that there's bad and good people – I want to soften people toward this idea that we all do fucked-up things, and it's not about not doing them or not punishing people for them. It's about finding ways to heal. Shame is not conducive to healing. Punishment is never going to help people heal. It's cruel and violent."

The book focuses on several abstract concepts, from queerness and shame to resilience found in grief. It's a haunting look at how surveillance often does more harm than good.

However, in the end, the book is about hope. "The kid provides a nice foil for Kris as well, because the kid doesn't take any shit," Crane said. "She is so stubborn herself and from a very young age has all these ideas of who she is and what treatment she will take and what she isn't going to take. Kris can see that spirit in the kid. That's helpful for her in dealing with the shame. There's another option, there's someone who doesn't let the system shame her."

What will they do next?

Crane's fans hopefully won't have to wait ten years for the next novel. They're already working on a second book, although it has a different tone than the first.

"I'm working on a Queer basketball novel," they said. "I know that sounds like a weird book after this one, but I played basketball my whole life. It's about the desire and the eroticism of playing a sport with another person. The sexiness of collaborating with someone really good at something you're also really good at and you love."

Crane plans to continue writing LGBTQ+ literature. "I don't even write straight stuff at all," they said.

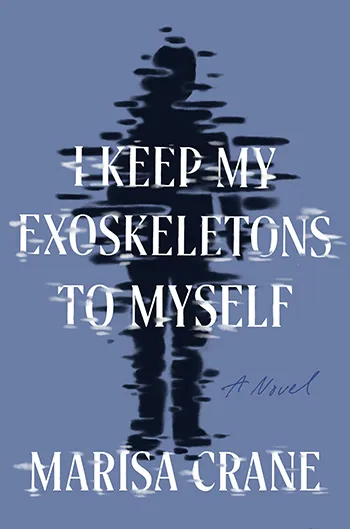

I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself is available in stores now.