BAYARD RUSTIN: A LEGACY OF PROTEST AND POLITICS

Edited by MICHAEL G. LONG

© 2023 NYU Press

$27.95

256 pages

Somehow, it seems, in the discussion about Martin Luther King and the leadership he brought to the civil rights movement, certain things are left out. In the case of Bayard Rustin, says Michael G. Long, editor of a new set of essays on the man, the record needs to be corrected.

His mother was still a teenager, and unmarried, when Rustin's grandmother helped deliver him in the spring of 1912. The boy's father refused to acknowledge him, so his grandparents gave him a family name and raised him in their Quaker faith.

Still, alongside the peaceful, gentle mandate of that religion, young Rustin experienced Jim Crow segregation. His grandmother left a major impact on him, teaching him compassion, kindness, and generosity – she reared him to do the right thing – but they lived in Pennsylvania, where racism was common and the Klan maintained a nearby presence. As if that wasn't difficult enough, Rustin realized he was Gay, which was illegal then.

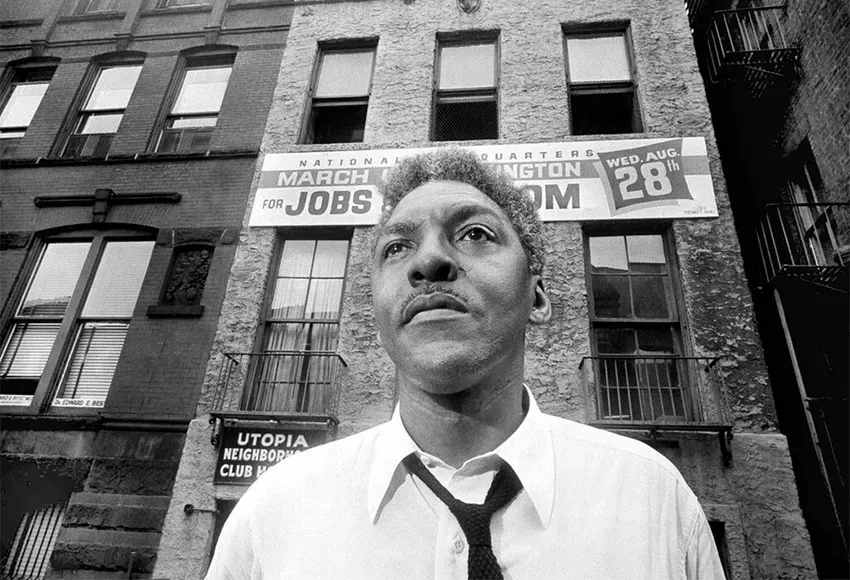

At that point, though, he had seen many wrongs around him, and he became an activist. He also worked for justice as a speaker and organizer; at one time, he'd embraced communism but eventually became a socialist. By his own admission, Rustin was jailed more than 20 times and served on a chain gang for several months – but even then, his nonviolent Quaker beliefs emerged, and he befriended his jailers, gaining their respect.

By the time he met a young preacher named Martin Luther King Jr., Rustin was well versed on civil rights work. He had direction, contacts, and the organizational skills the movement needed.

And yet, he was willing to let King take center stage...

As a collection of essays, Bayard Rustin has one flaw that probably can't be helped: it's quite repetitive. Each of the essayists in this book wrote extensively about Rustin's work and legacy, but there just doesn't seem to be quite enough about the man himself – perhaps because, as Long indicates in his introduction, history left him more in the background. This means that the nearly two dozen contributors to this book only had so much to go on, hence the repetition.

Even so, if you look for Rustin, you'll find a fair number tales about him, and this book has a good portion of them. Readers will be entertained, confounded, and pleased by what they read here. It's like finding treasure you never knew you needed.

This book needs to sit on the shelf next to everything written about Dr. King, as an essential companion to any volume about the civil rights movement.