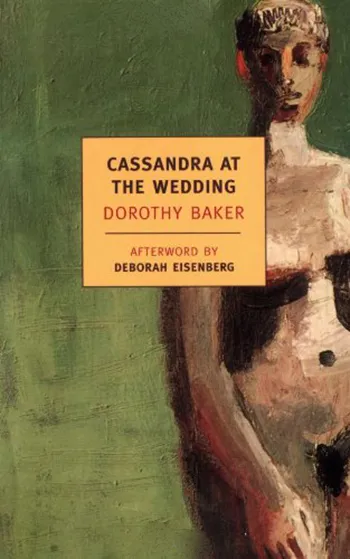

CASSANDRA AT THE WEDDING

Dorothy Baker

© 1962, 2012 New York Review Books

$17.95

256 pages

Content warning: Suicide

If you have any friends who are part of the New York literati scene, you've most likely heard of Cassandra at the Wedding. While not strictly a pulp novel, it has many of the same elements: suicide, forbidden doctor-patient relationships, dead moms, alcoholism, skimpy bikinis.

Books like Cassandra at the Wedding fall into the "literature" category mostly because their main characters are more intentionally unlikeable. And there's anxiety. Lots of anxiety.

To briefly summarize, Cassandra is a Berkeley grad student living the grad-student life of endless grading, avoiding her dissertation, sleeping around, and drinking too much. She goes back east to attend the wedding of her twin sister, Judith, who has been living in New York.

Cassandra is extremely torn up about her sister's nuptials, mostly because she hates that Judith is living her own life. Cassandra attempts suicide the night before the wedding. She is revived by her sister's soon-to-be-husband.

The ceremony goes on. Cassandra then walks onto the bridge she's been thinking about driving off of since the beginning – and throws her sock off it instead. It's a metaphor or something.

It's easy to see why many New York snobs like this book. New Yorkers love a narcissist – and Cassandra is a narcissist par excellence. It also falls into the territory of the also very New York neuroses-as-stand-in-for-intelligence. (I'm going to put this out there: being a dick doesn't make you brilliant, no matter what yet another Fox sitcom says. Go to therapy and learn some goddamn empathy.)

Possibly why this became such a pandemic must-read is that it deals with two pandemic-relevant issues: grief and the struggle of being stuck while the world around you moves on.

To wit, Cassandra and Judith's mother, Jane, had recently passed. Cassandra dealt with the guilt of not wanting to live but having her whole life ahead of her, compared to her mother, who so desperately wanted to live but could not.

Judith, on the other hand, moved out of her and Cassandra's shared apartment and went to New York, where she found a fiancé, created a life, and moved on.

So Cassandra is now stuck in their old apartment with a piano that was solely played by her sister, grappling with all the pieces of their shattered family. She finds herself unable to go forward or to pursue anything she truly wants, whether that's to be a writer or to date women.

It's the struggle of living in a society that hinges on the nuclear family. Women can only ever be half of a whole. Cassandra's world doesn't allow her the option of Gay coupledom. Instead, she feels that her only refuge from a heterosexual pairing is how society has trapped her before, as half of a twin set, which she's now in danger of losing.

Many of my Queer friends and I have struggled with an extended adolescence like Cassandra's. While our straight friends often settle down early (arguably, too early), we can be stuck in second puberty – and if you're Trans, literally. This second coming of age takes time: Time to discover, experiment, and sleep around. Time to shave my ahead in the bathroom sink while I get yet another beautifully calligraphed wedding invitation and question my choices.

Cassandra is only able to regain herself when her therapist, who she has a crush on, tells her she's several times the girl her sister is. This is based on a single conversation her therapist has in the hallway with Judith. This second-wave feminist tactic plays to Cassandra's narcissism – and works.

In the beginning, Cassandra looks into a bar mirror and is shocked by seeing her sister look back at her in the reflection. At the end, she sits with her sister at a bar, after the wedding, and sees them separately, even though they are dressed identically (another decision Cassandra made because she couldn't stand the thought of an event without her at the center). The reason she's able to make the distinction is by erasing her sister's individuality. Her sister is no longer Judith; she's a bride, a servant to conventional patriarchy, happy only because she doesn't have Cassandra's tortured genius. Great.

There's one moment that serves as a beautiful synecdoche. After Cassandra attempts suicide, Judith's husband revives her by performing mouth-to-mouth. Judith walks in and thinks at first that he is killing her sister, but then realizes he's saving her. Both twins are afraid of what it would mean to sever their codependent connection. The end of this pairing is a type of death, but it's also the only opportunity either of them have to really live.