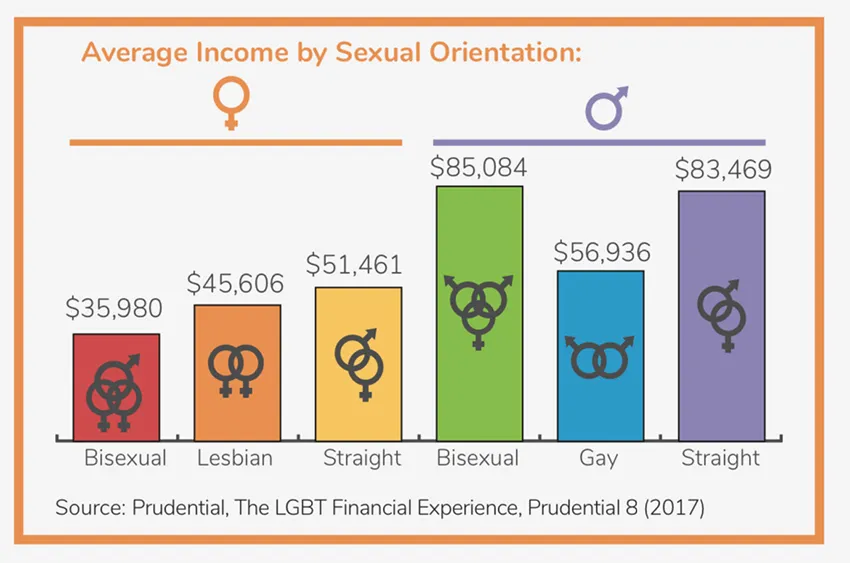

Despite decades of social and political progress, Queer people in the US continue to experience disparity in wealth and income compared to cisgender and heterosexual people. Research conducted by several sources in the last decade identifies an overall gap: Queer people earn $0.90 for every $1.00 earned by cisgender and heterosexual people. These disparities vary further according to racial and ethnic background, as well as between Queer cisgender people and Transgender people.

Using data gathered from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a 2021 analysis by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, "The Wage Gap Among LGBTQ+ Workers in the United States," found that of 7,000 full-time, Queer workers in the US, earnings were about $900 weekly compared to $1,001 for the average US worker. Troublingly, the analysis found that "LGBTQ+ people of color, transgender women and men, and nonbinary individuals earn even less when compared to the typical worker."

According to this analysis, poverty rates among Queer people reflect this trend, with about one in five Queer adults living in poverty. "In particular, the poverty rates of transgender adults (29%) and cisgender bisexual women (29%) in the US tower over those of other groups. Furthermore, Black (40%) and Latinx (45%) transgender adults are more likely to live in poverty than transgender people of any other race."

Causes of income inequality

In addressing the causes of these disparities, the Center for LGBTQ Economic Advancement & Research (CLEAR) analyzed multiple sources of research and determined that the wealth gap between Queer people and cisgender and straight people was caused by four contributing gaps in financial health: income and savings, access to financial information, public policy, and disparities in the market.

• Lack of savings and assets. CLEAR determined that Queer people, despite sometimes higher-than-average educational attainment, are more frequently underemployed, with lower-than-average pay, and are thus less able to save or purchase assets. This extends to homeownership and retirement savings, with Queer people being only 75% as likely to own a home and much less likely to hold an individual retirement account (18% to 35%).

• Lack of research data. Research data concerning Queer financial well-being is sparse. CLEAR calls this information gap one of the main contributors to Queer wealth inequality. In a 2014 article, "HDMA Data Offers Clues in Discrimination Against Gays" for American Banker, Mark Fogarty describes the conundrum: "There is, no doubt, prejudice against LGBT applicants. But there's not a lot of data to show how much." CLEAR also cites a 2016 World Bank report, which found that "huge gaps in research and data on LGBTI experiences persist in every country, blocking progress toward inclusion and the realization of human rights for all." This report points to blind spots in existing data, which fails to address issues such as accurate size estimates of the Queer community, public opinion on Queer communities, the impact of Queer inclusion in economic development, the impact of laws that make Queer people more vulnerable, and the impact of the multiple identities held by Queer people that affect their economic experiences (race, class, gender, ethnicity, etc.).

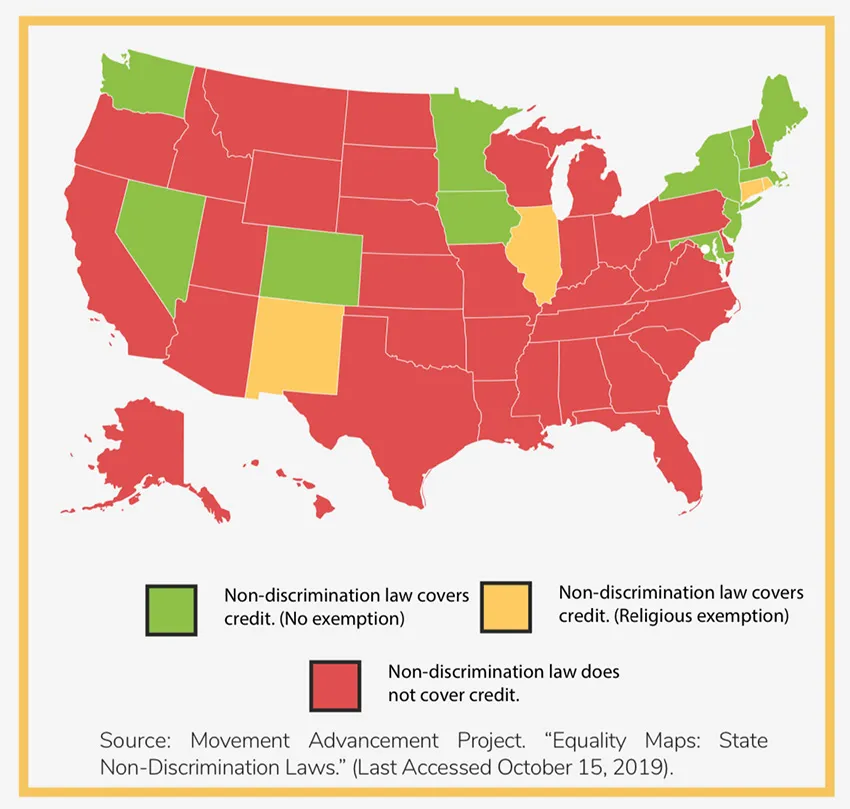

• Lack of legal protection. In the US, Queer people lack federal protection from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender expression. However, there exists an uneven patchwork of state, county, and municipal laws that protect Queer people from unjust employment, housing, credit, and public accommodations practices. Even among states with protections, some contain religious exemption laws that can be used to discriminate against Queer people.

• Uneven access to goods and services. Calling it a "market gap," CLEAR points out how discrimination against Queer people in the marketplace exacerbates the wealth gap. This includes access to credit, borrowing, and favorable interest rates. Mortgage data from the Federal Reserve studied by researchers at Iowa State University showed that same-sex couples seeking mortgages were denied 73% more frequently than heterosexual counterparts, and as a whole, overpaid by an estimated $86 million per year in higher interest rates, averaging 0.2% higher. Additionally, one in three (32%) Queer student loan borrowers in 2018 reported discrimination from a financial advisor or professional.

CLEAR also described the particular impact structural policies have on Transgender communities: "Trans and GNC customers, in particular, are singled out and denied banking or credit services because of harassment or unfair and outdated policies requiring customers to produce multiple forms of matching identification to open accounts – and to obtain court-ordered name changes to manage accounts in their preferred name."

The impacts of Queer income inequality

Across the board, disparity in income and wealth correlates to negative outcomes in other areas: education, health and quality of life, social well-being, and community vitality. CLEAR's report points out that such outcomes necessitate resources directed toward social and health services, and negatively impact productivity and output, as well as the effectiveness of investments in human capital.

Though Queer income inequality is first and foremost a problem that affects Queer communities of all demographics, it is a particularly destructive problem for Queer and Trans people of color.

Furthermore, it is not merely a problem that affects Queer communities. The effects erode the long-term stability of the US economy, job and labor market, and standing within the global economy.

These studies and reports demonstrate that in order to address the Queer income gap, future efforts must increase and renew emphasis on employment and public accommodations nondiscrimination policies. In light of the recent Supreme Court decision 303 Creative LLC vs. Elenis, this fight must include federal legislation as the end goal, along with pressure for state and municipal legislation across the country.