Generation gaps are nothing new, but with technology advancing quickly and the pandemic keeping people of all ages apart, isolation and loneliness have risen sharply in the United States. The Goldsen Institute of Washington has been working to address that problem with its Legacy Letters program, which blends research-based and trauma-informed methods to help build lasting bridges between the generations. Its second session begins on January 26, and signups are open.

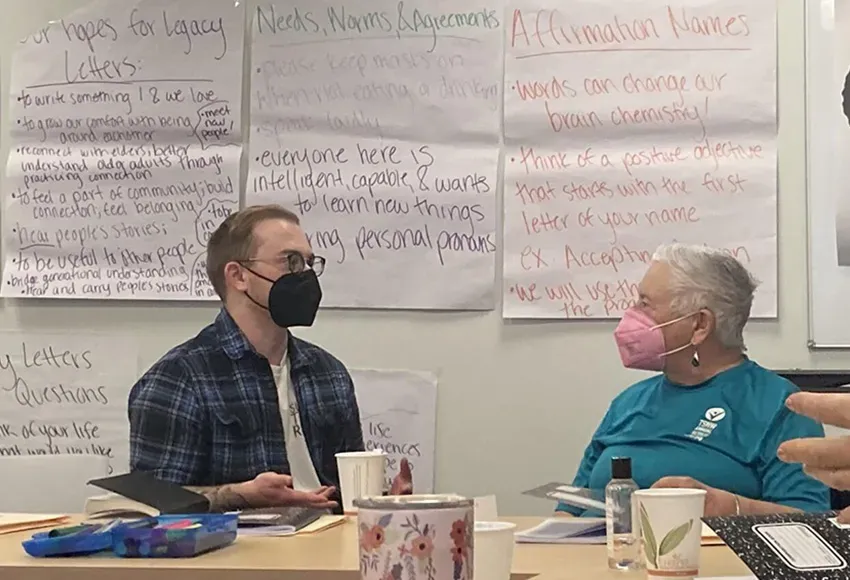

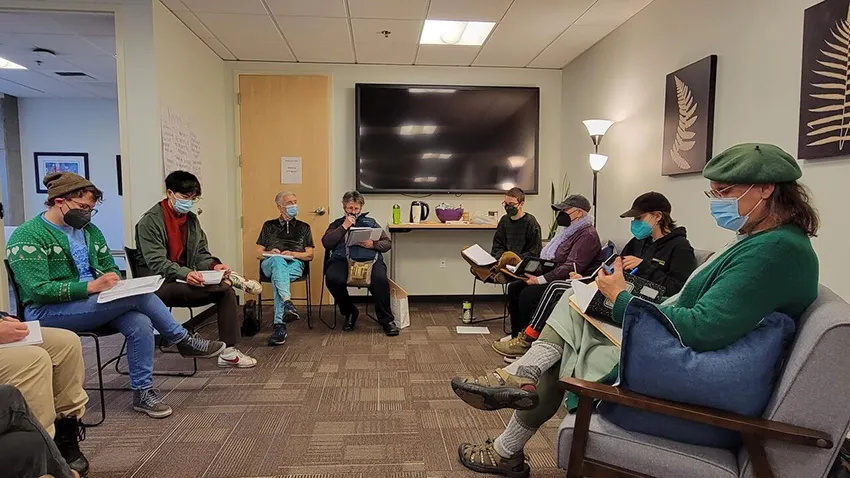

AgePRIDE Healthy Generations, an arm of the Goldsen Institute, has already one run of its Legacy Letters programs. It brought together elders from the Southeast Seattle Senior Center and teenagers from Franklin, Cleveland, and Rainier Beach high schools for five sessions of conversation, reflective writing, and public speaking, culminating in a personal letter to other generations.

Program manager Laura Culberg shared the institute's findings over Zoom. "One of the things we've learned through the research is that older adults – particularly underserved or more marginalized older adults – have higher rates of isolation and loneliness," she said.

On an emotional level, it's not difficult to see why that trend is a bad thing. But research makes it even clearer: the Harvard Study of Adult Development found that people middle-aged and older were three times more likely to be happy if they were engaged in caring for and developing younger generations.

"We live in a really age-segregated society in this country," Culberg went on, "so there are very few opportunities to integrate like that."

One might wonder, then, what's in it for the younger people. As it turns out, after the pandemic, their need for connections might be even greater. "The first time that we [ran the program], we actually found that the younger adults – the teenagers in this case – had higher rates of loneliness than the older adults," Culberg said, referring to follow up surveys.

Aislinn Conroy is facilitating the Legacy Letters program now, "but I'm not a researcher," they said in a phone interview. "I work on the translational action side." ("Translational" refers to applying research in ways that directly benefit people.) Culberg is the one guiding the participants in person, observing their growth, and "measuring the magic," as Culberg put it.

"It's just so wholesome," Conroy said. "It's the most wholesome job that I've ever had because my purpose is to encourage people to bond and create conditions where people feel comfortable being vulnerable. And they do that."

Conroy is certainly the person for the job; they have a background in trauma processing. Of course, a process this delicate doesn't always go off without a hitch, especially when many participants are gathering in public for the first time in years.

"It will come to nobody's surprise that ageism affects us at a cultural level, and it shows up in our sessions together," Conroy said. "But I wouldn't say it's a challenge so much as a part of what makes it interesting. It creates really rich discussions."

"For example," they went on, "in the South Seattle program, we had an extended conversation about pronoun usage, because what tends to be different between younger folks and older folks is that the vocabulary that they use is totally different."

Those who visited family for Thanksgiving, even in a fairly progressive household, might have heard a joke or two about gender identity from older relatives. But you might have also gotten a look confusion from an older Queer person at the mention of demisexuality.

Generational differences in vocabulary, Conroy said, are in some ways wider in the Queer community, "where younger folks are like, 'Why can't you just get it right?' And older folks are like, 'We're trying.' But there's a deeper story there."

Younger Queer people might not fully grasp the weight of what older generations have gone through.

"Sometimes I think that, especially with the Silent Generation (born between 1928 and 1945), they see these younger folks that are really out and open, and there's a sense of pride," Conroy said. "But also, they didn't get that. They grew up when Gay marriage was illegal, so it's complicated."

"But what's really special is that it's such a small group, and it's really a create-your-own-adventure type of program," they went on. "So we get to make space to have those kinds of conversations."

Each session may be small, but as the program grows, AgePRIDE will hold reunions open to participants of all past events. Far from a detached form of education, Legacy Letters intends to build lasting relationships – and so far, Culberg said, it seems to be working.

"I think part of seeing someone as a person is understanding them within their context," Conroy said, "and within their lived experience."

Young, old, or in between, you can find out more about AgePRIDE and the Goldsen Institute at https://goldseninstitute.org/agepride/, and sign up for the LGBTQ-specific winter session of the Legacy Letters program at https://redcap.iths.org/surveys/?s=AD7KCK34YEWJJ934/. The program begins at the UW Russell Hall Building on January 26 next year.