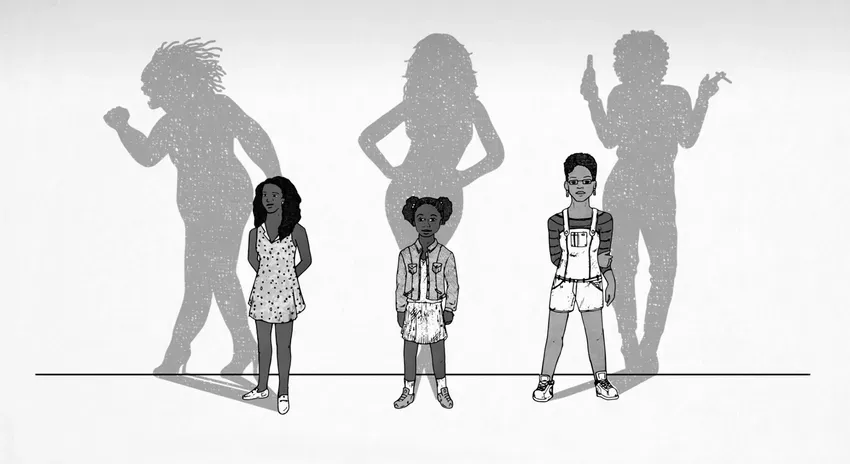

Social norms. The unspoken law dictating acceptable and appropriate behavior. They place the expectations for your social group directly on your shoulders before you can realize what it would mean not to fit in that box, or that there is even a box to fit into. At ages as young as five, girls in our country are being judged and labeled "too grown" for things that would classify other children as immature, outspoken or even just cute.

The 2013 report Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls' Childhood, published by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, states that "Black girls are viewed as more adult than their white peers at almost all stages of childhood, beginning most significantly at the age of five, peaking during the ages of 10 to 14, and continuing during the ages of 15 to 19." Views like these leave us to wonder what exactly is the standard for children's behavior, and who is the childhood model truly intended to reflect?

The study's participants were 74 percent white and 62 percent female with 69 percent of them holding a degree beyond a high school diploma. The results primarily show adults expect Black girls to be further along developmentally during mid-childhood and early adolescence than their white peers – and to need less nurturing, protection, support, and comforting. They are also expected to know more about sex and to be less expectant of male protection than white girls.

This occurrence of reduced or removed consideration of childhood as a determining factor in Black youths' behavior is referred to as "adultification." The adultification bias placed on young Black girls robs them of their childhood. It is a culmination of labels like "Sapphire," "Jezebel," and "Mammy" that hypersexualize them and link young girls with "unfeminine" and aggressive behavior, against an expectation of self-sacrifice.

Childhood is a social construct most refuse to admit is influenced by race and is something most people seem to agree on as a stage of innocence – until Black children are the subjects. In the 2017 follow-up research conducted by Georgetown Law, teachers are recorded describing Black girls as very mature socially but not academically, one even saying, "They think they are adults too, and they try to at like they should have control sometimes." These are the types of statements made when a Black girl's journey for independence is viewed as a threat or challenge to someone else's authority.

Nationally, Black girls suffer the consequences of the harsh judgments that accompany these biases. They are five times as likely to be suspended and account for 28 percent of school referrals to law enforcement and 37 percent of in- school arrests. These biases are what lead law enforcement officers, trained in de-escalating serious and deadly situations, to shoot and kill young Black girls.

Fatal consequences

Ma'Khia Bryant was a 16-year-old child involved in a fight when Officer Reardon arrived on the scene.

His bodycam footage shows Reardon's first instinct in the commotion between these girls is to draw his weapon. Bryant is seen holding a knife but there is a moment when the officer is close enough to grab her by the arms. The problem is his hands are already full. Were his hands free he could have grabbed and disarmed the child.

However, the officer's inability to recognize the aggressor in front of him as a child with a weapon put the girl on the other end of Bryant's knife in a dangerous situation. Reardon's adultification bias created the predicament that rendered him unable to save the lives of both these girls and made him feel it was justifiable for deadly force. He fires four shots at Bryant as she lunges at the girl in front of her, killing Bryant almost instantly.

"The results of our research suggest that Black girls bear the brunt of a double bind: viewed as more adult than their white peers, they may be more likely to be disciplined for their actions, and yet they are also more vulnerable to the discretionary authority of teachers and law enforcement than their adult counterparts," the study's authors conclude. "Only by recognizing the phenomenon of adultification can we overcome the perception that innocence, like freedom, is a privilege."

For more information about adultification bias and how you can help counter it, visit www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-inequality-center