Nothing could have prepared me for this particular student's story. I was in my third year as a teacher in a mental health program for children and adolescents. Every day, I would greet new students and say goodbye to old ones.

I would estimate that about a third of my students at any given moment were Queer. Most of those faced steep challenges with their families, especially parents who refused to acknowledge the students' pronouns, chosen names, and gender identities, or whose religious beliefs opposed their sexual orientations.

"Joshua" was admitted to the program one Thursday morning and was in my first class of the day. Once a sunny and outgoing 12-year old who had come out in sixth grade and presented as Gay, he didn't face these challenges per se, but instead another common set: he had been severely, collectively, and relentlessly bullied by his peers in an affluent, conservative, suburban school district outside of Fort Worth, Texas.

He had become withdrawn, bitter, and self-hating, and had resorted to self-harm and self-destructive behaviors. It was clear to me, the therapy team, and his parents that Joshua's mental health challenges were a direct result of the bullying and harassment he faced as a Queer preteen.

His stories horrified me. Reviewing his intake files was one of the most enraging experiences I encountered in my nearly decade-long career as an educator. The worst aspect of his account wasn't merely the brazen cruelty of Joshua's peers or the severe mental health impact it had on him (four suicide attempts by the age of 12 is four too many), but the complacency of his school and community regarding his mistreatment.

In some ways, Joshua was lucky: He wasn't alone. He had parents who advocated for him and were able to seek treatment, and eventually transferred him to a more supportive school. Even with these resources, however, he and his family had to face how his former school both officially and unofficially sanctioned the mistreatment of Queer kids, and how the community around him normalized the attitudes, beliefs, and social structures that made that mistreatment inevitable.

Abetting bullying

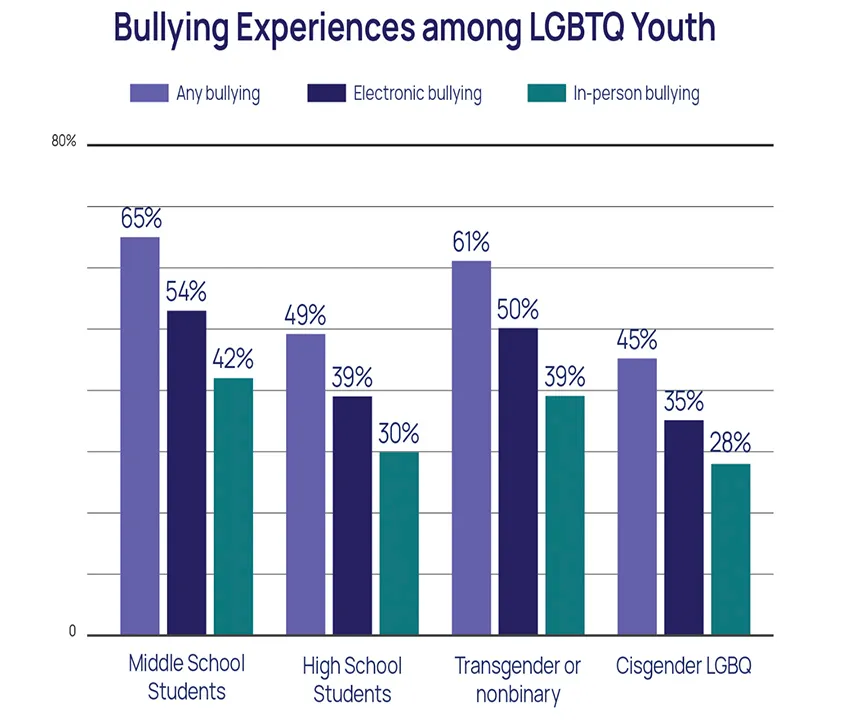

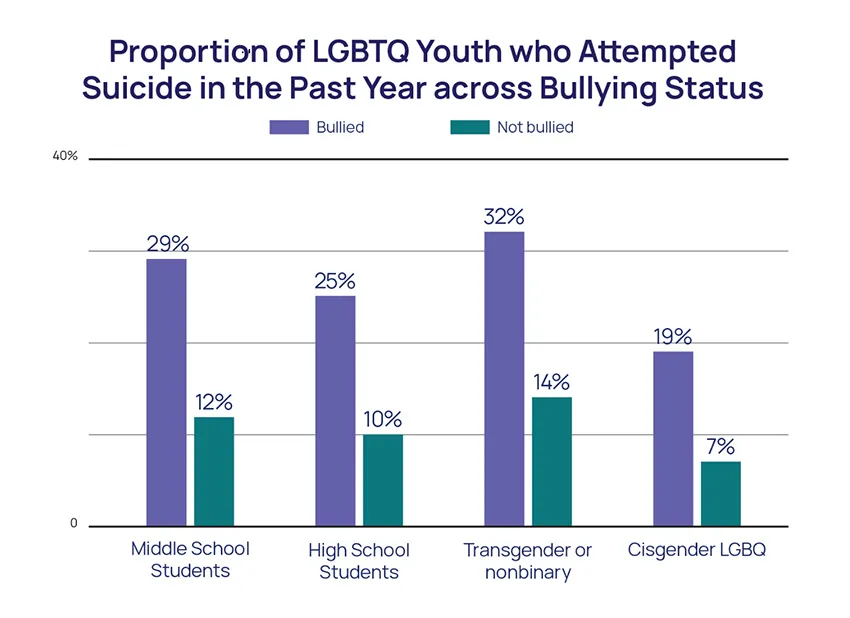

Tragically, Joshua's struggles are not an isolated case. In a brief published after its 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health, the Trevor Project, a Queer student advocacy organization, found that not only did the majority of Queer youth (52%) who were enrolled in middle or high school report being bullied either in person or electronically in the past year but that Queer students who reported being bullied in the past year had three times greater odds of attempting suicide.

The heartbreaking case of Nex Benedict, the Nonbinary teen in Oklahoma who ended their own life after being attacked by classmates in February, fits the same pattern that caught Joshua in its web of violence, harassment, and neglect. In Benedict's case, reactionary political forces created a climate of hostility and discrimination in Oklahoma schools that culminated in the teen's victimization and subsequent suicide. Joshua's case looks eerily close, save for the insistent interventions by his well-resourced parents.

In order to address school bullying of Queer teens, we have to acknowledge an uncomfortable truth about the way that it reflects the attitudes and behaviors of the adult world: kids bully kids because adults – and the institutions they build and run – bully adults.

Schools that refuse to understand how institutional power aids and abets the social hierarchies that build them will, without exception, enable youth as they bully those considered less socially included. Bullying is how they rehearse for the social roles they're being prepared for, and those who bully are securing as high a place in that hierarchy for themselves as possible. Bullying arises from behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs that they learn from adults.

Kids who are bullied are taught how to be subservient to those with more privileged positions. When schools, parents, and communities fail to act in order to protect them from bullying, they endorse the social hierarchies that it reflects.

Joshua and Nex weren't just mistreated, they were allowed to suffer by schools that, implicitly or explicitly, believed that this violence was somehow just. The mentality in communities such as Owasso, Oklahoma, and the conservative suburbs of Texas is that the "right kids" – in the words of Oklahoma Senator Tom Woods, "that filth" – were being bullied.

These attitudes were further entrenched through the incendiary rhetoric pushed by Oklahoma Schools Superintendent Ryan Walters and his unqualified appointee to the Library Advisory Board, non-Oklahoma resident and Libs of TikTok influencer Chaya Raichik.

Our message as we combat anti-Queer bullying is that there is never such a thing as a "right kid" for such targeting, and that the tragic death of Nex Benedict and others were entirely preventable through adequate responses to violence, harassment, and discrimination. Yet the attitudes of the adults running the schools gave the green light for these incidents through the increased politicization and scapegoating of Queer and especially Trans kids.

As a Queer former educator, the experiences of bullied Queer children and youth hit close to home. They remind me of my years as a neurodivergent Gay kid in the Texas panhandle, my struggles with administrators and parents over "lifestyle" issues, and the many hours I've spent trying to support, guide, and mentor Queer students facing sometimes extreme challenges.

Whether they hit close to home or not though, these young people's pain should light a fire under us to make our schools and our communities safer for all.

The lives of our youth are at stake.