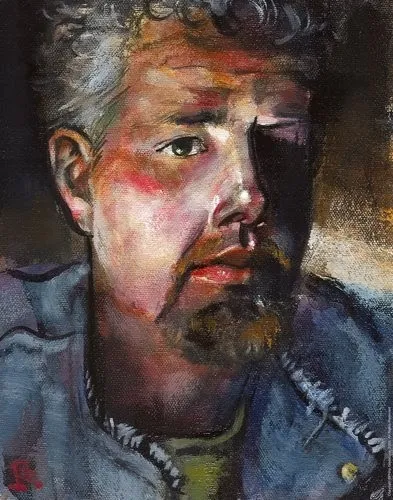

In the ever-evolving world of contemporary art, the enduring appeal of the well-painted figure remains strong. Few artists embody this more than Philip Gladstone, whose work bridges centuries of tradition with a distinctly modern sensibility. Gladstone’s paintings are intimate, honest, and deeply rooted in the exploration of identity — most often focusing on the male form not as an idealized or heroic subject but as a vessel for vulnerability, tenderness, and self-reflection.

Born in 1963 in Philadelphia, Gladstone had an upbringing that took him through Maryland, Maine, Florida, and Connecticut, following his father’s creative career as a graphic designer, illustrator, and cartoonist. Though Gladstone’s father never considered himself a “real” artist, he passed on a vast knowledge of art history and technique, offering an informal but rich education “at his knee.” Beyond these early influences, Gladstone is mainly self-taught, save for a formative summer at the renowned Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture at age 19.

Gladstone’s journey into the art world was unconventional. Before devoting himself entirely to painting, he spent nearly two decades as the owner and operator of a frame shop and gallery in Connecticut. In 2004, he began auctioning paintings on eBay and, within months, found that art could comfortably support him. By 2008, he had relocated to Maine, establishing his studio in a renovated barn — an environment that continues to foster his deeply personal and experimental practice.

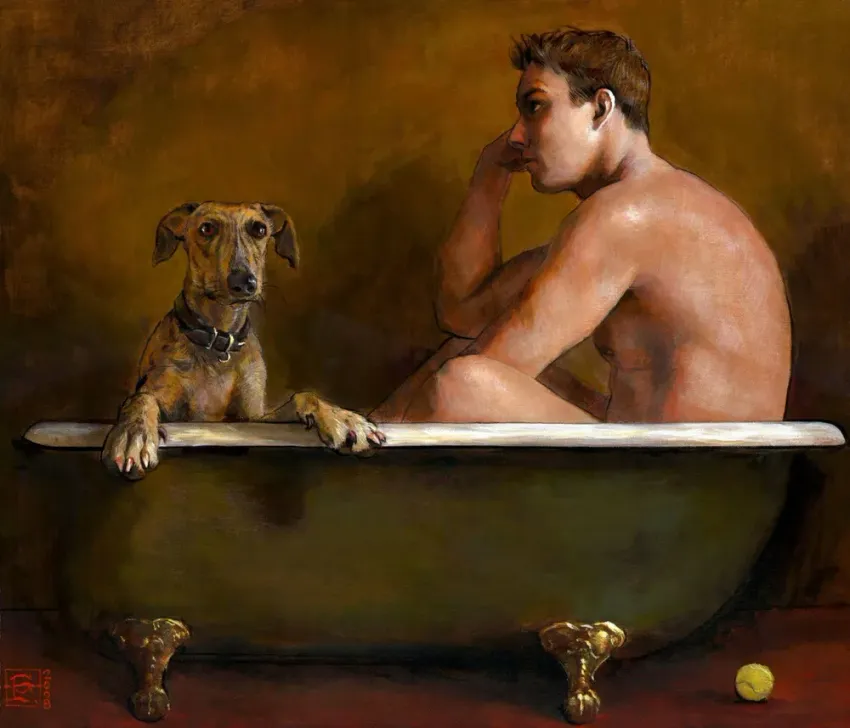

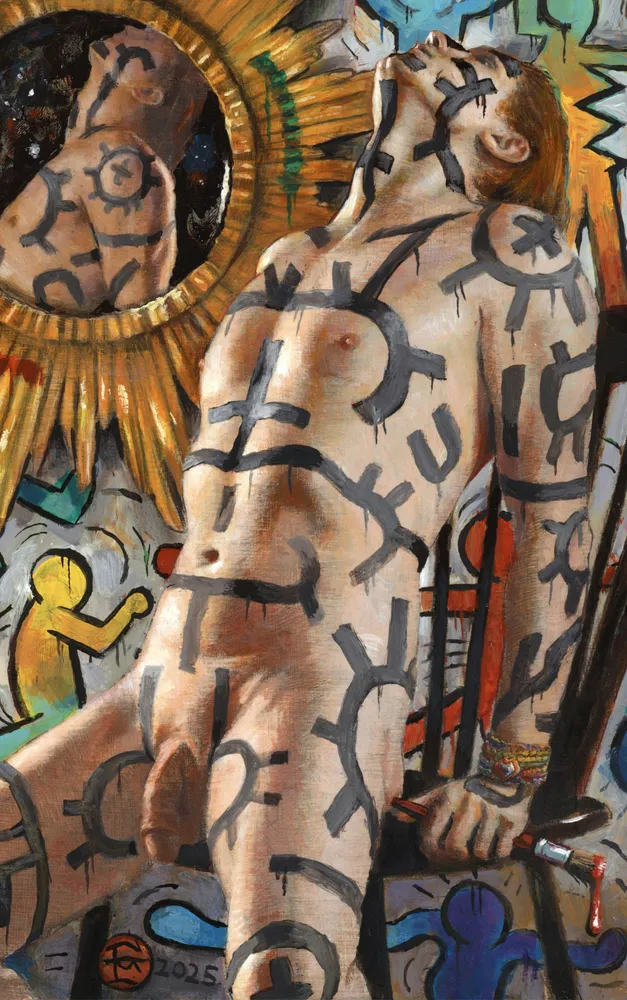

The heart of Gladstone’s work is his sensitive portrayal of the male nude. He moves away from the gods and warriors of art history, instead painting men in quiet, everyday moments — lounging on wrinkled sheets, bathed in morning light, or lost in reverie. His nudes are not objects of conquest or fantasy but stand-ins for himself and, by extension, the viewer. As Gladstone himself notes, “When you strip away the social constructs that seek to segment us, a clearer picture emerges, and our common humanity takes precedence over any differences.” His paintings invite viewers to see themselves — stripped of pretense, open, and vulnerable.

Technically, Gladstone’s skill is evident in his confident compositions, mastery of light, and subtle rendering of flesh. His paintings often recall the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and the compositional rigor of the Old Masters, yet they are unmistakably contemporary in their emotional resonance. Working primarily in acrylic, he employs a limited, earthy palette that heightens the sense of intimacy. Drawings and works on paper supplement his practice, capturing moments of immediacy and serving as preparatory studies and finished statements.

Gladstone’s art has found a particularly devoted following in the LGBTQIA+ community. Though he is not Gay himself, his honest and unguarded depictions of male intimacy have filled a void in mainstream visual culture, offering gentle, respectful, and relatable portraits of longing, comfort, and everyday beauty. As he reflects, “I’ve always felt a little out of place and ‘different’ since childhood… I’d like to believe that by exposing my innermost self in a sometimes painfully honest, unashamed manner through my work, I can help others to celebrate their differences — the beautiful things that make them unique — and be okay with being different.”

Gladstone’s artwork is increasingly showcased in prominent galleries, yet many collectors and enthusiasts discover it online. The interaction with his audience is crucial: “I spend hours working on each piece alone in a room, but it only truly comes alive through the eyes and minds of others once I’ve shared it.” This sincere exchange highlights the intimacy embedded in his paintings.

Frank Gaimari: What draws you to the male form repeatedly?

Philip Gladstone: I’ve often thought of my process as similar to that of a writer — perhaps a playwright — creating “characters” who act as stand-ins for myself. These characters may or may not resemble me, but they embody my deepest self. Because of this, they’re almost always nude, showing both their vulnerability and the feeling that the viewer is stepping into a private space.

When I paint a male figure, I’ve discovered that, as I work, I begin to feel as though I inhabit his mind and body — as if I am him — rather than simply being an outside observer. When I was young and learning to draw, I attended as many as three life-drawing classes a week. One particular model — a male dancer who could hold any pose for improbable lengths of time — had a lasting impact on me. The work we did together felt like an epiphany, because when I drew him, it felt as though I was drawing myself — a sensation I had never experienced before.

Later, when I had a family and a demanding job, time for painting became scarce, and models were hard to find. During those years, I often painted myself nude late at night using a mirror. I was the model for much of my work — nudes and otherwise — created in the early 2000s, at the beginning of my professional career.

FG: Your paintings of the male nude have found a devoted LGBTQ+ audience. How does it feel to know your work resonates so powerfully in Queer communities, and do you feel any sense of responsibility or kinship because of their responses?

PG: That quickly became evident from the reactions when I first showed my work, and it was a pleasant surprise to make that connection. As a straight man, I never would have presumed to be qualified to speak about, or to, the experiences of the Gay community. I was expressing myself — my state of mind — through the work. Yet, when you strip away the social constructs that seek to divide us, a clearer picture emerges, and our shared humanity takes precedence over any differences.

Gay men told me they saw themselves in my work, and some initially assumed I must be Gay, imagining that the feelings I was expressing were specific to that experience. They’re not, but as a rule, straight men in this culture seem to be terrified of admitting to those kinds of feelings, so I understand why it might seem that way.

In the early days, I sometimes worried about how a Gay collector might react upon discovering I was straight — would they reject me and view me as inauthentic, a charlatan? But the reality was quite the opposite: they were as surprised and delighted to discover our differences and commonalities as I was, and they welcomed the opportunity to explore them further. Our growing relationships became as meaningful, revelatory, and fulfilling to them as they were to me.

It was kinship, without a doubt — and yes, it brought with it a responsibility to maintain and nurture the honesty and integrity that made these connections possible in the first place, and to continue creating a unique world within my work where anyone might recognize themselves once they look beneath the surface.

The artist–collector relationship is, among other things, a partnership, with each doing their part to make the work possible and bring it to life. These relationships can be long-lasting and exceptionally intimate; in fact, my relationships with collectors have been among the most personal and fulfilling of my life. I am humbled and very proud that many collectors and fans in the Queer community have told me they see me as an ally, which I most assuredly am.

Like many artists, I have always felt a little out of place and “different” since childhood. I’d like to believe that by exposing my innermost self, sometimes in a painfully honest, unashamed way, through my work, I can help others celebrate their own differences — the beautiful qualities that make them unique — and feel at peace with being different.

FG: How do you respond to viewers who see autobiographical meaning in your work— especially those who assume the art reflects the artist’s identity?

PG: They’re a reflection of myself and an exploration of identity in the broadest sense, but not in a literal or narrative way. I’m not sure I would go so far as to call them “autobiographical.” For example, I painted a long series over several years that people refer to as the “Tubs Series,” depicting nudes in clawfoot tubs surrounded by their pets, musical instruments, and other props. The series proved very popular, yet I don’t have a clawfoot tub and have never taken a bath in one. What inspired the series was the feeling of wanting to crawl into a safe, cocooned space surrounded by my favorite things for comfort — and that’s really what the series is about: what it feels like to be me sometimes.

The “Museum Series,” while fun to paint and observe, also reflects feelings I’ve always experienced — confusion, exposure, and fear — in a world where I seek comfort, peace, and beauty yet instead feel threatened and intimidated by authority figures. In these paintings, the nudes represent me (often a much younger version of myself, as these feelings date back a long time), while the clothed guard often serves as my nemesis, perhaps shaming me simply for being myself.

About 20 paintings from the Museum Series were included in a show at the Las Cruces (New Mexico) Museum of Art earlier this year — a singular honor, made possible by longtime collectors who arranged to showcase their collection there.

FG: In what ways have the reactions and interpretations from Queer viewers shaped or surprised your own understanding of your paintings?

PG: They’ve often shown me, through their reactions and interpretations, what’s working and what isn’t in a piece — how well I’ve communicated and how close I’ve come to achieving a sort of universality. For me, communication is everything, so feedback is vital. I spend hours working on each piece alone in a room, but the work only truly comes alive through the eyes and minds of others after I’ve shared it.

FG: Do you find yourself consciously thinking about your audience’s expectations (Queer or otherwise) when you’re composing new work, or is the process entirely personal?

PG: I’ve always shared my work, for better or worse, in “real time,” with very little editing. This began in my early days on eBay, when I might list as many as three small paintings a day at auction. I’ve read that many performers — comedians, musicians, and others — describe being at their best when there’s a give-and-take with a live audience, and it’s a little like that for me. My audience’s expectations and reactions inform my work and often inspire new pieces.

I’d be lying if I said I never think about my audience’s tastes and expectations. I haven’t had an outside job for more than 20 years, and this can be an unstable way to make a living at times. So, if I have five pieces in progress and a big tax bill coming due, for example, I might prioritize finishing the one I think will be the most salable. Still, it remains a very personal process, and even after all these years, I can have a panic attack when it’s time to reveal a new piece. I put so much of myself into each one, and I can be very experimental, often taking risks rather than simply repeating past successes.

FG: What do you hope viewers, regardless of identity, first notice or feel when standing in front of one of your male nudes?

PG: Once viewers overcome what can be a kind of reflexive embarrassment that people sometimes feel when confronted by a nude work of art, I hope they realize that what they’re looking at is honest and real — and that they might even see themselves in it. From there, they can appreciate the draftsmanship, brushwork, and other aesthetic qualities. I once did a brief series depicting nudes sitting on toilets, simply for the challenge of creating pieces with that subject matter in a way that wouldn’t provoke laughter. While there were a few giggles, the overwhelming reaction was along the lines of, “I’ve been there,” so I believe I was successful.

FG: For younger Queer artists struggling to find their voice, what advice would you offer about putting their authentic selves into their work?

PG: Trust your instincts, overcome fear, and steer clear of compromise at all costs. Collectors and others will recognize the authenticity in your work. They will want to enter your world, watch you grow, and offer support and encouragement as you navigate your unique, sometimes treacherous, and uncertain path.

Philip Gladstone’s paintings do more than celebrate beauty. They encourage us to take our time, notice our own and others’ grace and vulnerability, and pay attention to the small moments that shape our modern lives. Each canvas lets viewers see the lasting importance of kindness, identity, and connection. This demonstrates that figurative painting, when executed honestly and skillfully, still has a great deal to reveal about who we are and the world we create together.

Philip Gladstone’s website: https://www.philipgladstonestudio.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/philip.gladstone.1

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/philipgladstone/

Frank Gaimari is an author, film reviewer, and actor based in Seattle, Washington. He lives with his husband and their two golden retrievers. Learn more about his work at http://FrankGaimari.com .

Support the Seattle Gay News: Celebrate 51 Years with Us!

As the third-oldest LGBTQIA+ newspaper in the United States, the Seattle Gay News (SGN) has been a vital independent source of news and entertainment for Seattle and the Pacific Northwest since 1974.

As we celebrate our 51st year, we need your support to continue our mission.

A monthly contribution will ensure that SGN remains a beacon of truth and a virtual gathering place for community dialogue.

Help us keep printing and providing a platform for LGBTQIA+ voices.

How you can donate!

Using this link: givebutter.com/6lZnDB

Text “SGN” to 53-555

Or Scan the QR code below!