Long before Sophie Lucido Johnson was an award-winning cartoonist for The New Yorker, back before she could ever even imagine herself as a published writer, she was a teacher in the New Orleans public school system, where her love of drawing seemed like more of a pastime than a potential career.

“I never thought I could make art. I think I believed that I wasn't good enough at it to be allowed to make it,” she said. “About 15 years ago, I went through a breakup with an artist, and I felt so sad that his art would no longer be in my life that I decided to say, ‘Screw it!’ and make it myself. What an amazing decision.”

Eventually, she decided to return to school to study art and writing. “It took two years to come to believe that I was capable of making comics and cartoons,” she said, “but I’m so grateful I let go of whatever cruel little voice was telling me I couldn’t.”

Once she let go of her self-doubt, the sky was the limit, and Johnson started drawing the clouds. “In December of 2018, in the bath,” Johnson recalled, “I was reading The New Yorker’s Puzzles and Cartoons issue and thought, ‘I want to be a New Yorker cartoonist. That is what I want my job to be.”

In 2019, she put her dreams to action and reached out to humorist and friend Sammi Skolmoski, and the two began collaborating. She taught herself to draw in The New Yorker style, and together they submitted ten cartoons to the paper. None were published.

Johnson didn’t let the rejection get her down. Instead, she took the feedback and continued to work on her craft. “I definitely drew more than a hundred cartoons before one was accepted,” she said. “When we finally got an OK, it was early in the pandemic, so I sat alone on my roof and drank a homemade gin and tonic and cried tears of joy.”

As a lover of “weird animals” — especially pigeons — Johnson’s work tends to focus on whimsy and visual realism. “It usually includes at least one bird and/or one cat and/or one echidna and/or similar,” she said. “I lean in particularly aggressively toward pigeons. A combination of Lynda Barry’s and Chris Ware’s philosophies was my greatest artistic influence, and I think about them every day. I even have them tattooed on my arm.”

Johnson also likes to use her work to focus on themes of found family and collective care. “I truly believe that we’re all living lives that are unnecessarily hard and isolated, because we have a distorted idea of what a family is supposed to be,” she said. “Through my work, I’ve talked to so many people who are living their lives differently, in vast ecosystems of love and care, and I can see possibilities for the ease and joy and meaning that so many of us are longing for. I want everyone to consider possibilities that we don’t see on TV yet.”

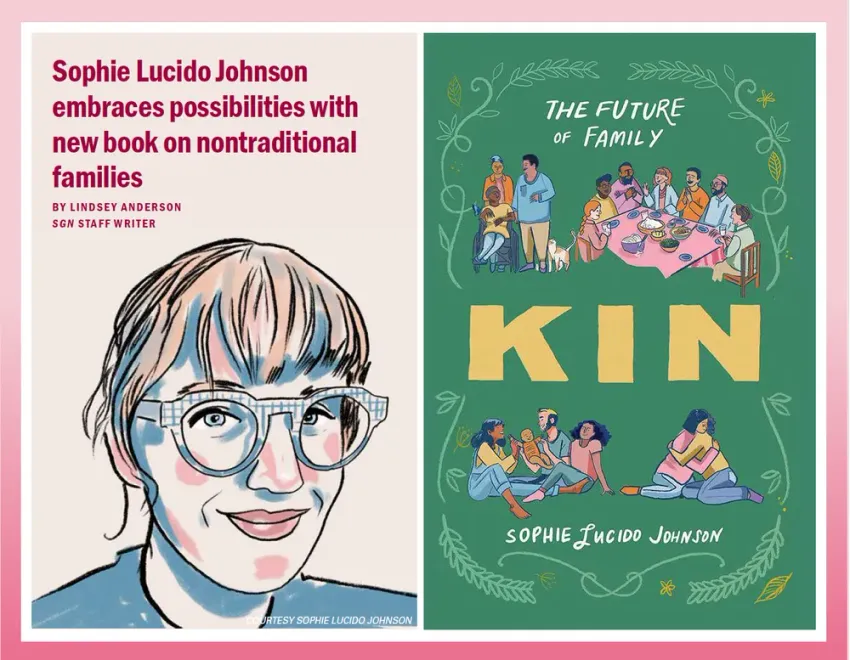

Her newest published book, Kin, takes a unique look into the different ways families can be. Johnson describes it as a “self-help book for people who are spread too thin, at their wits’ ends, scrambling to figure out how to do all the things they are supposed to do under late-stage capitalism to survive.” The book is inspired by her experiences during the pandemic, when Johnson and her partner lived with another couple. Both couples ended up experiencing pregnancy at the same time, and having a close-knit unit to help navigate the twists and turns of both journeys opened Johnson’s eyes to the unlimited capacity humans have for family.“

[We] were struck by how profound and great it was to be able to share things — including, eventually, our pregnancy journeys,” Johnson said. “Everything about cohabitating made our lives easier. Building on work I’d done in the past around polyamory and queerplatonic partnerships, I wanted to create a guide for people to find a version of the thing we all found.”

Kin dares readers to ask, “What does family look like to me?” and offers a radical answer. “It proposes a future outside of the nuclear family,” Johnson said, “based on close-knit connections among people who exist somewhere between ‘friend’ and ‘family’ — and it offers strategies for building intentionality around those relationships. It’s hopeful and practical.” The book also builds off of Johnson’s past work, centering polyamory and queerplatonic partnerships.

As a nonfiction author, Johnson devoted countless hours to research, devouring studies on relationships, cohabitation, and community. “My research taught me lots of new and surprising things!” she said. “Two statistics I find myself repeating a lot [are]: half of your close friendships turn over every seven years; and it takes more than 200 hours for someone to evolve into a close friend. Friendship takes time, and there are no shortcuts; and simultaneously, friendships shift and change over time, so you shouldn’t expect all of them to stay the same amount of close forever.”

The biggest struggle Johnson faced when working on Kin was finding families willing to speak candidly about their nontraditional structures. “Sadly, polyamorous family configurations are still not recognized as valid by so many people and groups,” she said, “and lots of poly folks worry (I think rightly) that they threaten their employability and livelihood when they come out in a widespread way.”

Still, Johnson hopes books like Kin will not only help raise awareness of the many forms family can take but also introduce people to the idea that family and friend dynamics don’t have to be as traditional as we’ve been taught. “I hope [readers] will be able to create ease in areas of life where they currently feel spread too thin or stretched to capacity,” she said. “I hope they not only understand but deeply believe that they do not have to be alone, emotionally or actively. And I hope they’ll have the tools to create extended networks of care and love that will move them safely and comfortably through whatever lies ahead.”

Just as Johnson once thought a life as a cartoonist wasn’t possible for her, many people limit themselves when they fail to open their minds to the possibilities of what can be. Kin is a book for people who are open to the idea that the traditional paths — whether starting a family, purchasing a home, or pursuing a new career — aren’t the only ways forward. If there’s one thing Johnson hopes people can learn from her, it’s to take chances and not let a desire for perfection hold you back.

“As children, we are not afraid of an image that doesn’t match the one in our heads; that’s a weird, grown-up thing that we learn over time,” she said. “If you’re interested in making art, make art. Life is short, and art is hot.”

Support the Seattle Gay News: Celebrate 52 Years with Us!

As the third-oldest LGBTQIA+ newspaper in the United States, the Seattle Gay News (SGN) has been a vital independent source of news and entertainment for Seattle and the Pacific Northwest since 1974.

As we soon enter into our 52nd year, we need your support to continue our mission.

A monthly contribution will ensure that SGN remains a beacon of truth and a virtual gathering place for community dialogue.

Help us keep printing and providing a platform for LGBTQIA+ voices.

How you can donate!

Using this link: givebutter.com/6lZnDB

Text “SGN” to 53-555

Or Scan the QR code below!